"Belief: Possibility and its Discontents" ASEEES Presidential Address

Written by Mark D. Steinberg

ASEEES Presidential Address: “Belief: Possibility and its Discontents”

Recently, I have been thinking about belief and death—for many reasons: personal, political, professional. The statement I wrote announcing this year’s theme began with the claim that “belief may be a universal human impulse.” Frankly, I worry whenever I use the word “universal.” Like many of us, and not least because of what we know of the histories of Eastern Europe and Russia, I am nervous about any totalizing category applied to social experience. Moreover, even if “belief,” in the broadest sense, might be universal, the claim is almost meaningless in the face of the endless variety of ways beliefs take form and act in the world. Like many of us, as a historian I am inclined see in human life less coherence than fractures, dissonances, and contradictions.

Death is universal, but of course there is nothing universal in how death is experienced or made meaningful. Most of us have also had personal encounters with death—in my case, that includes my wife Jane Hedges, who was known to many of you as managing editor of Slavic Review, four and a half years ago. I have also been thinking about the losses we experience every year in our profession.

As many of you know, Mark von Hagen passed away in September. A wonderful scholar, teacher, mentor, and person, he was a very involved member of ASEEES, including as president in 2010. Every year, influential and respected colleagues pass away. We remember them, here, with obituaries, memorial panels, in conversations. In this way, they are not lost into the darkness of death

But I have also been thinking about death and belief in a different way—more analytical, more philosophical, and certainly more political. We live in times in need of answers and actions, though the problems are often difficult to grasp in all their complexity and danger. And it is difficult to know what actions will matter. Here, I encourage you to read the texts of presentations at the Presidential Plenary, on “practices of belief,” which explores questions of dark realities, strong responses, and radical possibilities. (See the ASEEES web site)

In the midst of the death and devastations of what we have come to call World War I (the start of a count that still haunts our imaginations), the German-Jewish Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch began writing The Spirit of Utopia (a book that would be published in 1918). During World War II, as an exile in the US, he developed his research and his arguments into a huge study of the “utopian impulse” across cultures, histories, and genres of human expression, a book he called The Principle of Hope. This is not the place and time, and I am not the right person, to fully explain Bloch’s ideas. But I want to make two points that I find relevant to our work as scholars of Eastern Europe, Russia, and Eurasia—but also to our responsibility as citizens and human beings: subject-positions and perspectives that cannot be separated. (A point also made by presenters at the Presidential Plenary earlier today.)

The first is the one mostly closely linked to death but even more to the darkness that shadows so much of human history and life, what Bloch called “the darkness of the lived moment.” Bloch’s philosophical colleagues and friends—Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Hannah Arendt—had their own terms for this darkness and its relation to time and human experience. For Benjamin, history as we have come to experience it was (as he famously put it in 1940) a “catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage,” the dead upon the dead, a “‘state of emergency’ [that is]… not the exception but the rule.”[1] Or in Arendt’s words, written during the Cold War, “the scales are weighted in favor of disaster.”[2] Each of us, from our areas of study and from our own lives, may describe different stories and conditions on those scales, as that “wreckage.” But the imbalance and the ruins are hard to ignore.

The second point I take from Bloch is an attempt to answer the well-known question, “What is to be done?” Or rather, the still more difficult question, what is the point of challenging dark and harsh reality when it will always prevail? (Again: see also the discussions at the Presidential Plenary of skepticism and pessimism about the present and thus the future).

Which brings me to “belief.” Hannah Arendt, a tough-minded critic of fantasies, insisted that the refusal to accept reality as it has been given to us is essential for any political life: in her words, “the infinitely improbable … constitutes the very texture of everything we call real” (after all, she notes, human existence and survival is itself infinitely improbable) and so we must “look for the unforeseeable and unpredictable, to be prepared for and to expect ‘miracles,’ in the political realm,” even though “the scales are weighted in favor of disaster.”[3] For Walter Benjamin, we must try to “grasp the “splinters” and “flashes” of a “redemptive” “messianic time” open towards the future,[4] to “leap in the open air of history,” of possibility—which was how he defined revolution.[5] For Bloch, of course, this was the universal human “principle of hope,” the “utopian impulse” to “venture beyond” the limits and inadequacies of the world as it is, beyond the “darkness of the lived moment,” in order to grasp the “not-yet” (Noch-Nicht), to see the improbable “possible.”[6] If this is a definition of belief—it is not as faith for faith’s own sake, but a critical method for understanding what it possible and real.[7]

But I am not a philosopher or a theorist. I am a historian, and mainly of everyday life, of experiences and practices. And it is here that, for me, belief becomes most interesting.

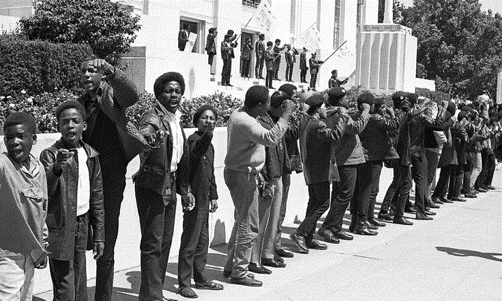

[IMAGE: SF 1967: summer of love] Literally here: in San Francisco, the city I was born and grew up in – a city with its own histories of violent brutality and cruel injustices (especially in how people of color, starting with the Native Americans, have been treated) and histories of belief and hope and action.

At this conference, many of you are analyzing stories of belief—both as expressions of hope and as pathologies. In looking at the program, I noticed papers on belief as a type of knowledge (including religion, science, ideology, myth, and philosophy); on expressions of belief (from artistic forms to political practices); on the performance, imagery, and sounds of belief; on the construction of social relationships around the assumed affinities and enmities of nation, ethnicity, class, gender, and sexuality… i.e., around communities of belief); and on consequential and revealing beliefs about such existential matters as sex, nature, death, and time.

Importantly, many panels and papers explore disbelief, including the refusal to believe what one is told to believe by one’s own community.

Belief has haunted my own work: not least, because it has haunted and inspired and troubled the people I have studied: employers and workers who believed it was possible to build “moral communities” (the title of my first book) of care and respect across class lines—and those who recognized it was not; the powerful belief among many workers that human beings have the absolute, even sacred, right to be treated, and to live, as befits their natural dignity as human beings: the right to “zhit’ po-chelovecheski”; a “proletarian imagination” (the title of my second book) that envisioned, with emotion and intellect rooted in both working-class experience and cultural encounters, a world where modern urban and industrial life enriched lives rather than debased people, where nature and civilization were not in opposition, and, above all, where the human personality (that key word in Russian history: lichnost’) flourished; urban writers, especially journalists, who obsessively described the “darkness of the lived moment” at the start of the 20th century, but as a critical method, as an answer to despair, to pessimism; and, most recently, people who were sure that 1917 was that rare, infinitely improbable moment (“sacred time”) when, as many then said, they were experiencing “resurrection” and “salvation,” a “time of miracles.”

Allow me to make this even more personal. The personal, we know, can be political too—and perhaps a source of analytical insight. As some of you know, I met my wife Jane at an ASEEES meeting (then AAASS) in Columbus, Ohio in 1978. And, if that were not unforeseeable and unpredictable enough, ASEEES has played a role again in my personal life: I mention this in case you did not know (and perhaps need to know) how romantic our conventions are! I have found love again—with someone I have known since we were both students in Leningrad in 1984, but with whom I have kept in touch at ASEEES meetings (thanks in large part to friends I also mainly see here).

Slightly less personal (at least, less likely to make me blush) is the work of my son, Sasha, known to millions (literally) as Sasha Velour—who, among other connections to our field, spent a year in Moscow, on a Fulbright Fellowship, studying for an MA with a focus on contemporary Russian political arts. At a very personal level, Sasha found in transgressive, queer performance a way to process and transform her own demons, the darkness in her own spirit and experience: including the death of his mother. Famously, Sasha became a bald drag queen as a way to embrace Jane’s chemo-therapy-caused baldness, but also the celebrate Jane’s refusal to hide her baldness, to emphasize the beauty, the “fierce beauty,” of a bald woman, of looking reality in the face. Of course, this is not only about personal darkness.

Sasha has explicitly embraced the utopian power of drag (always there but rarely articulated): in her words, from an interview with the Guardian newspaper in October 2017 (an appropriate year), “It’s all that darkness turned into power.”[8] Or, as she said in a more recent interview with Gay Times, “Drag is defined only by radical and ever-expanding possibility.”[9] Exactly: “ever-expanding possibility.” Again: utopian belief as critical method—but dressed fabulously.

I will conclude with one last story about darkness and belief. And I would reiterate this point: that belief in possibility against the prevailing lived darkness (historical, political, personal) is the foundation and essence of utopia as we need to understand it. (Or as Ron Suny said at the Plenary, echoing the philosophers I have been talking about: “we must not mistake the present for the future.”)

This summer and early fall I was in Odessa doing research on a new project of comparative urban history. Odessa, of course, has a history full of cruelty and suffering: including pogroms, occupations, crime, violence. Everyday life now is marked by a suffering economy, buildings and roads crumbling, homelessness, deadly fires, and still many prejudices and enmities. And yet, there are insistent assertions of radical possibility and belief, of the utopian principle of hope.

This is on display in the embrace of a new version of the Odessa myth: as a city of happy and tolerant cosmopolitan multiculturalism, a city of joyous transgression, where everyone is welcome (the popular interpretation of the gesture of the famous statue of the Duke de Richelieu, one of first builders of Odessa, who is facing the sea).

The recent moment that I want to pause over is Odessa’s Gay Pride Parade at the end of August. Almost every local religious organization—Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish—signed a letter (a shameful one, if I might editorialize) demanding that the mayor ban the parade as immoral, unnatural, anti-family, and thus anti-nation. (Or, using the term that Laurie Essig mentioned at the Plenary: as “gender ideology”).

Instead, to their credit, the city deployed hundreds of police and National Guard to protect the marchers. We marched through cordons of police. A few so-called “provocateurs” who tried to disrupt the march were arrested. But it was not all joyous and free. Dark reality was still there. At the end of the march, everyone was told to put away their rainbow flags and signs, dress more modestly, and not travel in groups on public transport. The risk of violence was very real—and the police would no longer be there to protect you.

We cannot and should not ignore the darkness of lived reality. Nor can we we ignore the pathologies of belief. It was, after all, belief (religious, normative, emotional, ideological) that led opponents to Pride to demand it be banned (as they have succeeded, of course, in Russia—and elsewhere in the region and the world). And much worse has been produced in history by belief, including ethnic cleansing, terror, and genocide. Moral righteousness, especially when bolstered by a belief in one’s place in universal history, can be murderous. And I don’t need to tell you that there are still leaders who speak of evil actors, traitors to the national spirit, enemies of the people. So, disbelief is also a necessary critical method.

When writing this talk, I found the hardest part was figuring out how to end: With the darkness? With “the principle of hope,” the “utopian impulse,” the leap in the “open air of possibility,” the flashes of messianic time, the improbable that is not the impossible? Perhaps I cannot figure out how to end because there is no end to the question: to reconciling “that which merely is” (as Adorno put it) with what we know ought to be. Perhaps I am uncertain how to conclude because this is beyond our power. As scholars, we can interpret the world, but we can’t change it. I don’t know. I do know, that being president of ASEEES certainly gives you no power to change reality, to tip the scales: sorry Jan (in case you were hoping)!

So, I will end with only this. An improvised riff, perhaps, relevant to our work as scholars. Belief is a method of thinking, no more and no less. A critical method—which can lead us beyond normative assumptions (including our own) about what is real, right, and possible. And that, I would like to think, is why we are here. As they said in San Francisco in the 1960s: for love not money. And that is worth a lot.

[1] Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” Selected Writings, 4 vols. (Cambridge, Mass., 2003), 4:389-411.

[2] Arendt, “What is Freedom,” Between Past and Future (New York, 1977), 165-69.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Benjamin, “On the Concept of History”

[5] Benjamin, “On the Concept of History”

[6] “Something’s Missing: A Discussion between Ernst Bloch and Theodor W. Adorno on the Contradictions of Utopian Longing,” in Ernst Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature: Selected Essays, trans. Jack Zipes and Frank Mecklenburg (Cambridge, Mass., 1988), 12; Ernst Bloch, Geist der Utopie (Munich and Leipzig, 1918), 9; idem., The Spirit of Utopia, trans. Anthony Nassar (Stanford, 2000 [from the revised 1923 German edition]), 3; idem., The Principle of Hope, 3 vols. (Cambridge, Mass., 1995), especially 1:3-18 (Introduction) and 287-316 (“Summary/Anticipatory Composition”).

[7] Ruth Levitas, Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society (New York, 2013). See also Frederic Jameson, Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions. (New York, 2005).

[8] Kathryn Bromwich, “Sasha Velour: ‘Drag is darkness turned into Power,’” Guardian on-line, 29 October 2017. www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2017/oct/29/sasha-velour-drag-is-darkne...

[9] Sam Damshenas, “Sasha Velour on deconstructing gender and what it would mean for drag,” Gay Times on-line, 14 February 2019. www.gaytimes.co.uk/culture/118580/sasha-velour-on-deconstructing-gender-...