Summing Up Poetry: A Case Against Packaging

Ainsley Morse, Dartmouth College

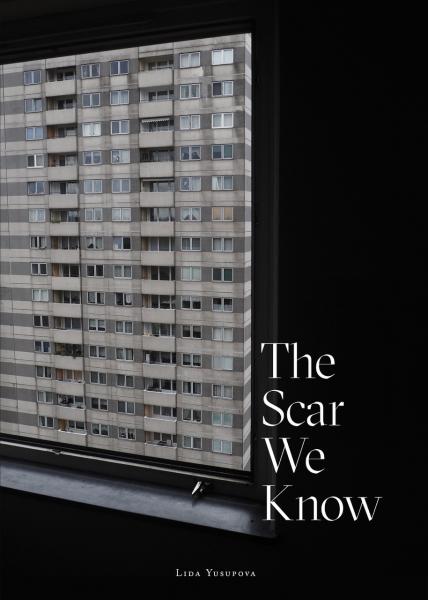

During the pandemic year I worked on a couple of poetry-translation projects: F-Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry, an anthology of work by twelve contemporary feminist poets/poetesses (isolarii, 2020, co-edited with Galina Rymbu and Eugene Ostashevsky) and a book by one of those poets, Lida Yusupova (The Scar We Know, Cicada Press, 2021). Working on these books was extremely illuminating and rewarding, and they have been well received. F-Letter may have gotten more attention and press than any other translation project I have worked on. While I’m glad to have helped to bring this poetry to a global audience, I am ceaselessly bemused by a process that often involves marketing and politics as much as literature.

During the pandemic year I worked on a couple of poetry-translation projects: F-Letter: New Russian Feminist Poetry, an anthology of work by twelve contemporary feminist poets/poetesses (isolarii, 2020, co-edited with Galina Rymbu and Eugene Ostashevsky) and a book by one of those poets, Lida Yusupova (The Scar We Know, Cicada Press, 2021). Working on these books was extremely illuminating and rewarding, and they have been well received. F-Letter may have gotten more attention and press than any other translation project I have worked on. While I’m glad to have helped to bring this poetry to a global audience, I am ceaselessly bemused by a process that often involves marketing and politics as much as literature.

While in grad school a fellow student once chuckled that you could look at the many different poetic groupings of the early twentieth century (Futurism, Cubo-Futurism, Ego-Futurism, Acmeism, Symbolism, etc.) as “brands” competing with one another on the art market—proof, perhaps, that Russia was well on the way to full-blown bourgeois capitalism. Whether or not this model works for the pre-revolutionary era, we certainly have full-blown capitalism in U.S. book markets today. I’ve become painfully aware of the fact that translation is a hard sell; poetry is even harder (it is no accident that both are often published by small independent presses like isolarii and Cicada). People do not have a lot of time. What sells? Loud voices, clear messages (topical and/or “eternal”), compelling personal stories. To a certain extent, this market logic has influenced what people teach as well.

In literature’s inevitable intersections with global politics, writers from distant lands ruled by bad politicians often find themselves in the role of hero—beacons of freedom, brave Davids against the menacing Goliaths of repressive politics. It is an old story (a Cold story), but it keeps working for the publishers—and other defenders of vaunted Western democracy. This means American readers, who tend to need some hand-holding when it comes to literature in translation, often expect a specific kind of narrative, a certain type of voice, from foreign authors. These expectations, compounded by publishers’ calculations, can turn reading into a form of conscientious consumerism, where buying a book written by a certifiably repressed person automatically renders the reader more enlightened.

While there is nothing wrong with effective and legible packaging per se, I usually think of (and try to teach) poetry as something that cannot be summarized or easily defined; a way of thinking with language that produces more questions than answers. Some book covers, meanwhile, give you an answer right away—even if the book is actually full of questions.

F-Letter is a tiny-format book with a shiny, bright red cover. Rymbu’s introductory essay explains the recent (re-)emergence of feminist discourse in Russophone writing and argues for its urgency and relevance in contemporary Russian society. Rymbu and Oksana Vasyakina, the best known of the feminist poets in Russia, take up the most space in the volume. One of the two long cycles by Rymbu, “My Vagina,” was at the center of an internet scandal in summer 2020 that saw Rymbu both attacked and praised for using explicit anatomical language in poetry. “My Vagina” was an entirely political gesture: Rymbu wrote it in support of Yulia Tsvetkova, an artist and activist who has been subject to arrest and intimidation for her body-positive art and activism. In the introduction, Rymbu points to close engagement with physicality as one of the hallmarks of the new feminist poetry. While this is patently true, women (and queer) poets have been “writing the body” in Russian long before the recent emergence of feminist-identifying poetry.

The other ten poets in the book demonstrate a wide range of poetics, only some of them engaging directly with feminist politics. Alongside brutal evocations of gender-based violence from Egana Dzhabbarova, Elena Kostyleva, Lida Yusupova, and self-deprecating feminist humor from Stanislava Mogileva, there is Vasyakina’s sweeping meditation on her father’s death from AIDS, writing poetry, and battling the patriarchy. But you will also find the baroque, sexually and philosophically charged hellscape of Lolita Agamalova’s “Dilige, et quod vis fac,” which in turn contrasts sharply with the intimate, domestic poetics of Ekaterina Simonova and the many things left unsaid by Nastya Denisova (just to give a few examples).

All anthologies suffer from issues of selection and space, and this one is especially tiny: it only has room for one or two poems per poet. I am thrilled that Yusupova’s The Scar We Know came out virtually simultaneously with the anthology, because it offers a much fuller spectrum of her work. Yusupova—who has not lived in Russia since 1994—is a complex and idiosyncratic personality with a trajectory that has lately run parallel to feminist concerns. At 54, she is the oldest poet in the anthology; some of the younger poets have engaged her as a forerunner of the movement, although she only started writing poems with an identifiably feminist agenda within the last five or so years (basically on the same timeline as the movement itself). In one of the poems in The Scar, “The Center for Gender Problems,” the speaker confesses her real motivation for seeking out Petersburg’s so-called Center for Gender Problems in the late 1990s:

I’m not that interested in writing for their feminist newsletter though maybe I am but not that much not that much and it’s so important so important to me to meet lesbians I want to meet feminists too but lesbians are more important to me because maybe maybe after I meet them a new life will begin for me I came to the center for gender problems but not to write for feminism I came only for myself yes I came here because I want love and sex with a lesbian yes I came here for love that’s my problem I came here for love

Even though these lines come in a breathless rush of unpunctuated prose, they can be read from different angles. Yusupova’s poem covers the feminine lyric subject, physical threats against women, and lesbian sex (as well as the difficulty of finding the language, especially poetic Russian language, to express such an experience). But there’s also plenty to say here about the cultural shifts of the 1990s, and stereotypes and hedonism and irony.

The Scar We Know is hardly an exhaustive selection of Yusupova’s work—it barely scratches the surface of her enormous, ongoing cycle of “Verdicts” (poems built from the grisly material of Russian court documentation), and does not include any of her early work from the 1990s or prose experiments. Still, the book does justice to a poet and her complex trajectory, one that cannot be distilled into a keyword. I wish each of the anthology poets could be similarly well represented—but who is going to publish ten more books of contemporary poetry in translation? And what about all the fascinating poets who are not in anthologies, some of whom actively resist labels and affiliations?

The Scar We Know is hardly an exhaustive selection of Yusupova’s work—it barely scratches the surface of her enormous, ongoing cycle of “Verdicts” (poems built from the grisly material of Russian court documentation), and does not include any of her early work from the 1990s or prose experiments. Still, the book does justice to a poet and her complex trajectory, one that cannot be distilled into a keyword. I wish each of the anthology poets could be similarly well represented—but who is going to publish ten more books of contemporary poetry in translation? And what about all the fascinating poets who are not in anthologies, some of whom actively resist labels and affiliations?

I found out about Yusupova from the poet, visual artist, and set designer Dina Gatina, who gave me Yusupova’s book Ritual C-4 in 2013. Gatina, who grew up in the small city of Engels on the Volga river, writes despairing, obscene, and hilarious poems and songs, tightly constructed, bursting with subtle and incisive wordplay, and often apologetically elliptical. She has also been writing (and illustrating) female bodily experience and, by all means, raging against the patriarchy, for years:

писька, такая мохнатая coochie, so furry, so fuzzy

писька, невиноватая coochie, you’re not to blame

писька coochie

что мир так устроен вокруг that this world is built like it is

Still, it is hard to imagine her work in a feminist anthology. The F-pismo brand of feminism is theoretically inflected. Leading figures like Rymbu and Vasyakina, as well as other writers affiliated with the collective, have variously engaged with feminist and queer theorists like Hélène Cixous, Monique Wittig, and Judith Butler. Gatina’s years of association with the theory-mad (and male-dominated) scene around the Petersburg literary journal Translit left her permanently exasperated with attempts to apply theory to daily life (otherwise understood as the stuff of poetry).

There’s a Russian expression: chto eto takoe i s chem ego ediat—literally, what on earth is that and what do you eat it with. F-Letter offers a beautiful range of poetic diversity, served under the familiar sauce of political repression and (feminist) activism. But how do you “serve” a poet like Gatina—or Anna Glazova, or Polina Andrukovich, or Elena Guro (or Fet, for that matter)? With my colleague Rebekah Smith from NYU/Ugly Duckling Presse, we decided to host a series of Zoom readings and conversations by Russophone women poets (some featured in the anthology, some not) that would highlight just poets—acknowledging them as women and inviting them to speak to this status, but without any idea what they might say or choose to read. What resulted was riveting, controversial, articulate, evasive, breathtaking, brief, capacious—and impossible to summarize. (But available to watch on the Jordan Center YouTube channel.)

Ainsley Morse teaches in the Russian department at Dartmouth College and is a translator of Russian and former Yugoslav literatures. Her research focuses on the literature and culture of the post-war Soviet period, particularly unofficial or “underground” poetry, as well as the avant-garde and children’s literature.

Note: This blog first appeared in the June 2021 NewsNet.