In Search of the “Perfect Collection”: Armenian Studies Collections at the UC-Berkeley Library

by Liladhar R. Pendse, UC Berkeley

This piece was originally printed in the June 2018 NewsNet. Click on the link for additional resources.

As an interdisciplinary area of inquiry at a historical crossroads of language, religion, ethnicity, and empire, Armenian Studies poses particular challenges for librarians. As libraries attempt to build modern research collections attuned to the present and future needs of Armenian Studies scholars, it is important to solicit the input of both researchers and of professional associations devoted to the field.

Introduction and Statement of the Problem

As my colleagues and I try to understand and analyze the unattainable ideal of a “perfect collection that supports Armenian Studies,” several key questions emerge. Historically speaking, existing collections at the majority of the North American universities are a function of personnel investments and financial investments over time. How can one define and measure the impact of such collections on the community of scholars and students in the face of differing philosophical collection building approaches and methodologies, often fraught with contradictions? How can a collection be built in the face of limited resources and relentless technological changes? Can one even aspire to build a “perfect collection” for a niche discipline such as Armenian Studies? For present purposes, I define Armenian Studies as an interdisciplinary field that is devoted to the study of Armenians, Armenia, Armenian diaspora communities, and the Armenian Genocide.

The definition of what constitutes the topos of Armenia has changed throughout history, which in turn means that the present day Republic of Armenia represents an important but geographically limited part of the historical Armenian homeland. In this paper, I briefly describe the challenges and opportunities that librarians encounter when they begin to assess their collections.

Background

The history of the development of the Armenian collections at the UC Berkeley Library remains understudied. The establishment of the Armenian Studies program at UC Berkeley in 1996 was a result of efforts a group of Armenian-American community members in Bay Area that led to the establishment of the Krouzian Endowment. In summer 2002, Professor Stephan Astourian became the Executive Director of the Armenian Studies Program and Assistant Adjunct Professor of History. He focused on building a comprehensive curriculum on contemporary Armenian history, language, social issues, and culture, which in turn encouraged the library to continue developing its Armenian collections for research and teaching purposes. It could do so by building upon its collection of rare Armenian books and manuscripts, many of them donated by Phoebe Apperson Hearst.

Skills, Challenges and Opportunities

Before my arrival in 2012, our library’s Armenian collections had evolved as an effort of collaboration between the curators, donors, and faculty members. There are several challenges that a library can face when it comes to developing Armenian Studies collections. It is difficult to find the qualified curators who are familiar with both Eastern and Western Armenian dialects, Armenian grammar and paleography, along with the working knowledge of Ottoman Turkish, Russian, Persian, French, and other languages that are used by the members of Armenian diaspora.

Although manuscripts, rare and common printed books, periodicals continue to remain the focus of many traditional collections, non-traditional formats such as ephemera and non-Armenian-language materials produced by local Armenian diaspora communities are increasingly of importance. Being transient in nature, if these are not preserved or collected systematically, they will be lost to the ravages of time. The development of rapport with the key community informants can be leveraged to enrich the library collections, through donors interested in helping a knowledgeable outsider in his or her collection development goals.

Upon my arrival at UC Berkeley, I conducted an environmental scan, meeting with faculty members in History, Slavic Languages and Literatures, and other departments who had an interest in Armenian Studies. Besides meeting with key faculty members, I also met with key members of the Armenian Alumni Association and solicited their informal feedback regarding their expectations for collection development. One of the issues that I faced was the fact that our Armenian Studies collection was primarily divided between two of UC Berkeley’s libraries, Doe and Bancroft. I also realized that the working relationship between the librarians at these two libraries was dynamic. It was a function of differences in understanding, vision and collection scopes, as well as perceived job-related responsibilities among the different curators and librarians. As a librarian who was responsible for developing the Armenian Studies collections at Doe Library, I focused on collaborative efforts with my colleagues at Bancroft.

I also made an effort to reach out and enlist the members of the local Armenian community in the Bay Area by attending several on-campus and off-campus lectures and events. This generated several donations of Armenian books that were published in Boston, Fresno, Glendale, and other parts of the United States in the 1950s and ’60s. My own experiences in dealing with the donors and well-wishers from the local Armenian diaspora community have been rewarding. I noted that the diversity of the Armenian diaspora in the world and specifically in the United States is so immense that there are unavoidable limitations on the possibility of building a so-called “perfect collection” for all stakeholders at any given institution.

The other decision that I made was to also collect born-digital Armenian Studies materials. This did not mean that I did not collect print materials related to Armenian Studies in various languages; I frequently collaborated with other Area Studies curators to collect materials that were published in their areas of responsibility, such as materials published in Latin America, the Middle East, etc. To date, at the Doe Library there are 1,603 print monographic titles in Armenian. However, not all of our Armenian-language books are held in our main stacks. A part of the collection is located in the Northern Regional Library Facility (NRLF), which serves as our off-site storage.

As of January 2018, there were 1,012 Armenian-language books held by the NRLF. Therefore, the total number of books with a publication date of 2010 or later in our Doe Library’s collection is 2,615. Out of these 2,615 books, since my arrival, I was able to purchase 412. This represents approximately 16% of the total number of titles added as a part of my strategy to rejuvenate our Armenian collections. There are currently several other libraries on campus to whom I refer Armenian titles that come in on the approval plan that I manage. I did not take into consideration these titles for the purposes of this introductory article.

As of January 2018, there were 1,012 Armenian-language books held by the NRLF. Therefore, the total number of books with a publication date of 2010 or later in our Doe Library’s collection is 2,615. Out of these 2,615 books, since my arrival, I was able to purchase 412. This represents approximately 16% of the total number of titles added as a part of my strategy to rejuvenate our Armenian collections. There are currently several other libraries on campus to whom I refer Armenian titles that come in on the approval plan that I manage. I did not take into consideration these titles for the purposes of this introductory article.

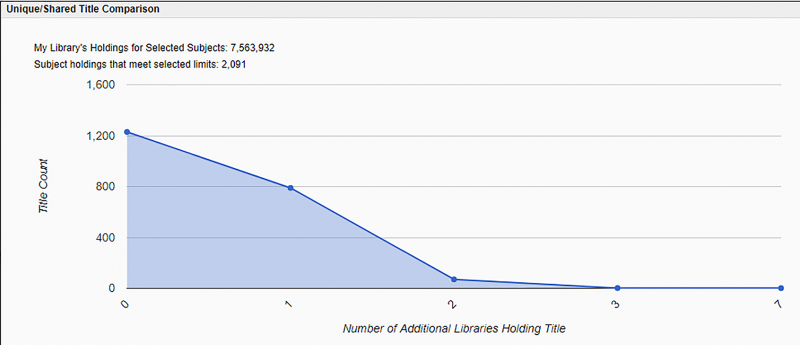

The other tool that I used to gauge the strengths of UC Berkeley’s Armenian Studies collections was OCLC’s WorldShare Collection Analysis Tool. The WorldShare tool allows us to analyze our collection for its uniqueness.

Leveraging Digital Resources

To return to the question of born-digital Armenian Studies materials, an important part of UC Berkeley’s Armenian Studies collection development strategy centers around the leveraging of current technological capabilities to harness and harvest relevant online content. To this end, I conducted a cursory survey of the digital assets at our library that were related to Armenian Studies. I also surveyed open-access Armenian Studies e-resources located at other universities. The Online Archive of California provides us with access to metadata about 299 Armenian Studies collections indexed in the OAC. Out of these, the UC Berkeley Library deposited 49 collections. For early Armenian manuscripts one can also use the Digital Scriptorium, as well as sources from sister UC institutions such as UCLA., Another readily available resource often overlooked by librarians is the collection of Armenian Studies materials at the Center for Research Libraries (CRL). Only last year the CRL announced the purchase of Armenian diaspora newspapers like Amrots, Arawot, and others. This was a result of my proposing the purchase of these important newspaper titles to CRL.

One way to distinguish one’s collections related to Armenian Studies would be to launch a new digital project that will be both sustainable and useful to the scholars of the future. In consultation with faculty members at UC Berkeley, for example, I launched a web-archiving project called The Armenian Social Organizations of North America Archive. The project selectively harvests and archives the web sites of a set of eighteen North American Armenian social organizations for posterity. The archived materials include born-digital documents, audio-visual clips and other aspects of these websites. The archive is publicly available at the following address: https://archive-it.org/collections/9254.

This project is not primarily intended to add to my strategies of creating a “perfect” Armenian Studies collection, but rather to preserve for posterity the websites of the Armenian diaspora in North America.

Lastly, I would like to share our Armenian Studies Library guide, which I created in an attempt to provide information about the UC Berkeley Library’s Armenian Studies collections as well as open-access resources. The guide is not a comprehensive pathfinder to Armenian Studies as an interdisciplinary area studies field, but it does introduce our students and faculty to currently available Armenian Studies resources.

Conclusion

This work highlights only a few of the issues that are associated with building, sustaining and developing Armenian Studies collections in the context of an academic library. I contend that the perfect collection of Armenian Studies materials cannot exist at a single institution, but will depend on linking of multiple collections that are scattered across institutions. Besides the financial climates of the “new normal” that we all encounter, the paucity of Armenian Studies programs, along with their interdisciplinary nature, sometimes places Armenian Studies collections on the periphery of Slavic and East European Studies as well as Middle or Near Eastern Studies. Also both the analog and digital Armenian manuscript collections in academic libraries are proudly displayed in a fundraising context, these often represent past acquisitions that date back several decades. It is advisable that librarians responsible for Armenian Studies collections should consider an alternative collaborative collection development strategy across the multiple US academic libraries.

Liladhar R. Pendse is a librarian for Slavic, East European, Caucasus and Central Asian Studies and Latin American Studies Collections at UC Berkeley. He also serves as a campus-wide coordinator for the Center for Research Libraries and contributes scholarly articles on Open Access in Eastern and Central Europe as well as on materials in less commonly taught languages.