Rightward Populist Rebellion in East Central Europe: Anxieties, Proselytization, and the Rebirth of Mythical Thinking

by Jan Kubik, Rutgers University/University College London

Editor’s note: This article is based on the President’s Address at the 2020 ASEEES Convention. It is not a transcript, rather Prof. Kubik’s reflections on a work in progress. Additionally, the complete article, including citations can be found in the January 2021 issue of NewsNet.

When in early 2019 I proposed the theme of the annual convention, “Anxiety and Rebellion,” I had no idea that the topic would become so much more relevant in 2020. The theme reflected my anxiety shared with many observers of the rise of right-wing populism in the world, particularly the increasingly bizarre and frightening spectacle of Trumpism in the US and the ascendance to power of right-wing populist parties in Poland and Hungary, both members of the EU. I expected neither the intensification of protest politics nor the explosion of irrationality, the process I call mythologization.

It is accepted in the literature that the rising popularity of populism and growing support for its political manifestations, most importantly populist political parties, is a reaction to various anxieties. I treat populism as a form of rebellion against political, cultural, or economic conditions that generate anxiety, while an intensifying wave of reactions to the populist upheaval is seen as counter-rebellions. If populism is a reaction to rising anxiety among some people, its emergence becomes a source of anxiety for others, and a cycle of reaction and counterreaction, also in the streets, commences.

What is populism? Following several authors, but particularly Cas Mudde, I define it as a type of ideology or discourse. It has two forms: thin and thick. The former has four features, the latter – five. It is important to assume that all four features of thin populism need to be present to classify a given ideological statement, political program, or discourse as populist. These features include:

1. Vertical polarization that sets “the people” against “the elites,” which are seen as separate and mutually exclusive groups or categories of people.

2. Antagonism exists between the two categories.

3. The whole construct is strongly Manichean (i.e., it is based on fundamentalist moralizing), which assumes that the essential feature of social/human reality is the struggle of the forces of good and evil and that any conflict/tension between these two groups is an instance of that fundamental struggle. The key implication of Manicheism is that political opponents of populists, construed as champions of the forces of evil, are – by definition – illegitimate or at least defective political actors, whose elimination from the public sphere needs to be rhetorically promoted and, if possible, enacted.

4. Finally, there is the idea that politics should be the expression of volonté général (general will). This idea helps to define and justify attempts to introduce in practice popular sovereignty, according to which the substance of (majoritarian) democracy trumps procedures (of liberal democracy). Moreover, the latter are seen as a nuisance if not an obstacle to the exercise of the people’s genuine will. This, in turn, opens a way towards the justification of authoritarianism as a form of rule.

If democracy, in a nutshell, is understood as the rule of people constrained by the rule of law, fully-fledged democracy is always liberal democracy. Ergo, authoritarianism can be defined primarily as a strategy of power exercise that removes or minimizes the rule of law and the system of institutional checks and balances.

5. Populists need to define ‘the people’ and when they offer such a definition populism thickens. The most common cultural resource employed in providing such a definition is a conception of national identity, usually derived from the concept of nativism. It serves to generate horizontal polarisation whose essence is the juxtaposition of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ people, the central distinction of exclusionary right-wing populism.

There are several ways to explain the rise of populism, but they all can be reduced to either two or four types of explanations. Inglehart and Norris analyze the dilemma culture or economy, while Eatwell and Goodwin write about four Ds: (1) deprivation (economic insecurity); (2) dealignment (of the political system that no longer properly represents peoples’ interests); (3) distrust (particularly of the elites); and (4) destruction (of traditional cultures providing existential security).

The same analytical scheme applies to sorting out various types of remedies or anxiety-reducing mechanisms that people may rely on to cope with the dramatically changing world. In a nutshell, anxieties can be reduced by: (1) making politics more responsive to people’s needs; (2) improving people’s economic condition by redistributing wealth more equitably; (3) reorganizing society to help people become more trustful of each other and the elite; and (4) redesigning culture in a way that would help people understand and operate in the increasingly alien world.

Whether and how some cultural remedies may alleviate but also exacerbate anxieties is a hugely important question that I do not have space to address. Instead, I want to focus on another distinction. In the broadly conceived cultural sphere, those who attempt to provide remedies have – by and large – two strategies to choose from: inclusionary or exclusionary. They can try to offer remedies applicable either to a broad and varied range of people or to a narrow, select category, for example members of “our” race, nation, or religion. Right-wing populists invariably employ the latter – exclusionary – type of strategy.

What do they do exactly? How does it work? By resorting to cultural remedial measures designed to reduce the anxiety, but only among those who can be classified as “us,” exclusivist politicians, such as right-wing populists, generate a range of consequential results. They improve their supporters’ self-perception by elevating “us,” putting “them” down, displacing guilt from “us” to “them,” and ascribing blame to “them.” They promise redemption. Finally, they explain ruling as an automatic and easy process, as long as the “people” trust the leader who is simultaneously “one of them” and a “chosen one,” and knows how to do “just the right thing.” A relationship between leaders and followers founded on such convictions inevitably leads to the intensification of authoritarianism in the political system.

There are several conceptual tools that can help us to describe and analyze the way cultural mechanisms employed by right-wing populists can and sometimes do alleviate their followers’ anxieties. One of them is what Arlie Hochschild calls emotion work; the other is mythologization, my sole focus here. The literature on the relationship and contrast between mythological and non-mythological, for example scientific, thinking is gigantic, but worth re-reading as it offers many tools that can help in dissecting mythologization that is so ubiquitous in today’s populist politics. I have already dusted off three old interpretive tools. First is the idea that myth is a disease of language. The second comes from Claude Levi-Strauss who was convinced that myths have “hidden” structures, which can be reconstructed via a systematic comparison of several versions of a mythical story. For example, once we uncover that initially concealed structure, we can see how the “deep story” so structured can help to deal with grand existential questions popping up in the minds of people tortured by anxiety. Third, it is useful to be reminded that myths pull people away from rational thinking (logos) towards evidence-resistant and emotion-ridden intellectual constructions (mythos) and this process enhances people’s belief in the efficacy of magic. Fourth, it is always important to remember that even in the most “modern” societies myths circulate in many areas of life, particularly in politics, and are often associated with ritualistic performances.

Not for a moment do I want to suggest that it is easy to cleanly separate mythical and non-mythical modes of thinking, rationality from irrationality, or that it makes sense to periodize social development by delineating various epochs on the basis of the centrality of mythical thinking in them, as was done by early evolutionary thinkers. Mythical and non-mythical modes of thought coexist, in various combinations, in all known societies. The locus classicus of anti-mythical thinking in the history of the West is the Enlightenment’s cult of reason and empirical observation, and yet, as Horkheimer and Adorno demonstrate in their Dialectic of the Enlightenment, Enlightenment tends to fall into a trap of its own self-mythologization. I share their and Leszek Kołakowski’s conviction that human societies cannot escape myth and mythological thinking but it is equally obvious to me that some modes of thinking and discourse are more saturated with mythology than others. Humans can try to follow paths of learning that respect the rules of rationality and empirical evidence (though these are historically situated and constantly evolve) or they can privilege thinking in terms of mytho-logics that are inimical to reason(ing) and the value of the ever-evolving empirical evidence, as in conspiracy theories. As Christopher Flood argues while comparing (political) theory and (political) myth, they both share “a similar function of enjoining its addressees to action,” but in different ways. “Whereas theory characteristically presents itself as logical argument to invite intellectual assent, political myth seeks to stimulate an emotional response through demonstration in the form of narrative.”

Right-wing populist and fascist ideologies are shot through with mythological modes of thinking. Right-wing populists are proselytizers who deliberately abuse the human mind’s predilection to engage in mythologizing. The definition of right-wing populism, presented earlier, includes at least three characteristics that invite mythologization: (1) the Manichean impulse to construe all conflicts as instances of the epic struggle between the forces of evil and the forces of goodness; (2) the exaltation of volonté général whose workings remain un- or under-specified, thus the whole concept becomes susceptible to mythical elaborations; and (3) the very concept of “the people,” who are seen as “unistitutionalized, nonproceduralized corpus mysticum,” stripped of the multitude of cleavages and sub-groups that characterize society seen through sociological lenses that – at their best – decrease mythologization.

To illustrate these general points, I will briefly reflect on two instances of mythologization detected in the discourses espoused by Polish right-wing populists. The first case is the transformation of “gender” from a descriptive and explanatory category of social sciences into a rhetorical figure driving the mythological construction of “gender ideology.” While more comprehensive analyses of this process are available, I am interested in it only as an instance of mythologization. A preliminary comparative analysis of several versions of the “gender ideology” tale reveals, for example, the existence of a deeper narrative structure, more or less fully realized in concrete retellings, as suggested by Levi-Strauss. The essence of this mythical structure is the relentless (Manichean) binarization of the picture of the world, a central feature of right-wing populist discourses that helps to construe and harden images of various “arch-enemies” of the people, including non-heteronormative people, “infidels,” or racial/ethnic aliens.

Despite the overwhelming scientific evidence that gender and non-binary specifications have sometimes varied, depending on a culture or time period, in the mythologized right-wing narrative it is binary, immutable, and inseparable from biological sex. “Gender ideology,” is dangerous – as its opponents argue – because its “real” goal is the destruction of “normal” societies, an inevitable outcome of the rejection of the “traditional,” binary concept of gender, which is closely linked to the traditional understandings of family and gender roles. It seems that the more popularized the scientific understanding of the complexity and diversity of sex and gender becomes, the more intensely mythologized it is in right-wing discourses. This is poignantly exemplified by associating gender with a cult of death. The slogan presented in Illustration 1 reads: “Gender kills identity, soul and body.” This case helps to see how mythologization is productively approached as a form of semantic hijacking, or as – as Müller or Barthes would have it – a disease of language.

Despite the overwhelming scientific evidence that gender and non-binary specifications have sometimes varied, depending on a culture or time period, in the mythologized right-wing narrative it is binary, immutable, and inseparable from biological sex. “Gender ideology,” is dangerous – as its opponents argue – because its “real” goal is the destruction of “normal” societies, an inevitable outcome of the rejection of the “traditional,” binary concept of gender, which is closely linked to the traditional understandings of family and gender roles. It seems that the more popularized the scientific understanding of the complexity and diversity of sex and gender becomes, the more intensely mythologized it is in right-wing discourses. This is poignantly exemplified by associating gender with a cult of death. The slogan presented in Illustration 1 reads: “Gender kills identity, soul and body.” This case helps to see how mythologization is productively approached as a form of semantic hijacking, or as – as Müller or Barthes would have it – a disease of language.

The second form of mythologization of right-wing populist discourse is associated with the demonization of the LGBT people. A neutral acronym “LGBT,” that serves to represent a variety of non-heteronormative and non-cisnormative identities, has been turned into a rhetorical weapon, for example by President Andrzej Duda who in a campaign speech called “the promotion of LGBT rights an ‘ideology’ more destructive than communism.” The influential Archbishop Jędraszewski of Kraków referred to LGBT as a “rainbow plague.” The use of a dehumanizing metaphor of plague that resurrects an anti-Semitic trope is striking; the construction of a mythologizing narrative around it is even more so. As Levi-Strauss has famously noted, bricolage is the preferred method of mythological construction. The method works more or less like this: let’s grab available symbols or discursive threads and themes, mix them up together, and try to use a new concoction to solve the problem at hand. Jędraszewski, whose goal is the delegitimization of LGBT people’s efforts to constitute themselves as a collective subject in the fight for recognition and equal treatment under the law, acted as a true bricoleur when he linked what he called “rainbow plague” with “red plague.” The latter phrase still has a powerful emotional resonance for many citizens of the post-communist world. It is also related to yet another mythological construct, “Cultural Marxism,” seen by the opponents of “gender ideology” and “rainbow plague” as the driving force behind the plague’s new, “rainbow” phase. In this myth-building bricolage, Soviet-style Communism and Marx end up being responsible for what a Catholic Archbishop sees as an illegitimate mobilization of the whole category of people (LGBT), a mobilization that he interprets as an attack not on tradition alone but also on the nation’s very existence.

Since 2015, when the right-wing populist Law and Justice party came to power in Poland, the mythologization of the public discourse intensified. Mythological constructions of “gender ideology” and “rainbow plague” have started influencing the nation’s (political) culture, in my judgement not only to generate a legitimizing cover for the right-wing populist government’s crusade to dismantle many elements of the previously established, liberal-democratic order, but also to sustain the level of anxiety necessary for a continuous support for populist traditionalists in power

There were several waves of protest against right-wing populism in Poland. The biggest began in the closing months of 2020. On October 22, 2020, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal ruled that one of the three provisions of the already restrictive Polish law regulating access to abortion was unconstitutional. The abolished provision allowed abortion when “prenatal examinations or other medical data indicate a high probability of serious and irreversible disability of the foetus or an incurable life-threatening illness.” This decision, by the Tribunal whose legitimacy is seen as dubious by many Poles and whose performance in November 2020 was assessed negatively by 59% of respondents (20% - positively), has immediately provoked intense counter-mobilization, arguably the biggest wave of popular mobilization seen in Poland since 1989. This protest wave followed two earlier ones. In the summer of 2017, Warsaw and several other places saw massive marches and rallies in defense of the constitution and constitutional order, threatened by a series of classical populist maneuvers designed to weaken the country’s system of checks and balances. The mobilization under the banners of restoring constitutional order based on legal rationality, rejected many mythologized stories peddled by the government to justify its actions. Earlier, in 2016, when women’s rights to control their own bodies came under attack for the first time during PiS’s term, women and their allies organized massive demonstrations under the banners of the Black March and Women’s rebellion.

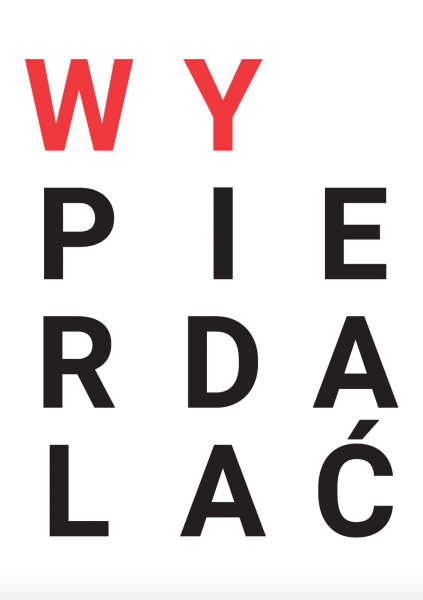

The massive 2020 protest wave surprised observers not only because of its ferocity and national scope, unprecedented since 1989, but also because of the omnipresent, inventive humor and the widespread use of profanity. One of the mildest slogans read: “Could you please fuck off” (“Bardzo proszę wypierdalać”). (Illustration 2). Days of protest were organized around many performances and displays aimed at rejecting the legitimacy of the ruling party by ridiculing its officials, actions, and ideas in literally hundreds of provocative, slogans. Many observers were taken aback by what they saw as excessively provocative and profane behavior of participants, particularly young women.

The massive 2020 protest wave surprised observers not only because of its ferocity and national scope, unprecedented since 1989, but also because of the omnipresent, inventive humor and the widespread use of profanity. One of the mildest slogans read: “Could you please fuck off” (“Bardzo proszę wypierdalać”). (Illustration 2). Days of protest were organized around many performances and displays aimed at rejecting the legitimacy of the ruling party by ridiculing its officials, actions, and ideas in literally hundreds of provocative, slogans. Many observers were taken aback by what they saw as excessively provocative and profane behavior of participants, particularly young women.

Observing this massive mobilization and the extraordinary, carnivalesque atmosphere the participants in these events created, I was immediately reminded of Bakhtin’s classical work on the significance of carnival. He wrote:

During the century-long development of the medieval carnival, /.../ a special idiom of forms and symbols was evolved, an extremely rich idiom that expressed the unique yet complex carnival experience of the people. This experience, opposed to all that was ready-made and completed, to all pretense at immutability, sought a dynamic expression: it demanded ever-changing, playful, undefined forms. All the symbols of the carnival idiom are filled with this pathos of change and renewal, with the sense of the gay relativity of prevailing truths and authorities (emphasis – JK). We find here a characteristic logic, the peculiar logic of the ‘inside out’ (à l’envers), of the ‘turnabout,’ of a continual shifting from top to bottom, from front to rear, of numerous parodies and travesties, humiliations, profanations, comic crownings and uncrownings.

There can be little doubt that the events of late 2020 in Poland showed that carnival and carnivalesque rituals of reversal have cathartic functions and may become sparks initiating an enduring cultural change, even if the immediate political effectiveness of carnivalesque protest may be low. It is, however, striking that under the impact of these protests and the botched governmental reaction to them, people’s positive assessment of the country’s top political institutions, such as both Houses of the Parliament and the President, dramatically declined in October and November of 2020.

What are the lessons I draw from this brief analysis? First, I am sure that while the rising popularity of right-wing populism can be easily seen as a remedy for cultural anxiety and/or economic insecurity, the rising tide of anti-populist mobilizations indicates that what one group of people sees as an anxiety-reducing remedy can be seen by others as an anxiety-inducing threat. If populism is rebellion, its opponents stage counter-rebellions. As a result, we see, at least for now, the ratcheting up of social tensions fed by the self-perpetuating dialectic of mobilization and counter-mobilization.

Second, I want to emphasize that in Poland, the US, and quite a few other places around the world, right-wing populists not only institute illiberal political solutions, but also engineer an incessant mythologization of their countries’ cultures. It is thus imperative that those who fear the collapse of liberal democracy need to find a way to restore people’s faith in science, logic, and empirical evidence and thus demonstrate that the confirmation bias inherent in mythological thinking can be resisted.

Third, laughter, mockery, irony, and irreverent anti-authoritarian language laced with profanity are insufficient tools of rebuilding trust in evidence-based and logic-respecting procedures, so central to the proper functioning of liberal democracy. But they constitute an excellent remedy inoculating people against the temptations of mythologization, because they undermine the façade of manufactured certainties and remind us that the uncertainties of reason are much healthier for democracy than the certainties of myth.

Jan Kubik is Professor in the Department of Political Science at Rutgers University and Professor of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London (UCL). He works on the rise of right-wing populism, culture and politics, and protest politics. Among his books are: The Power of Symbols against the Symbols of Power and Twenty Years After Communism: The Politics of Memory and Commemoration, with Michael Bernhard. He is also the Co-director (with Richard Mole) of two international projects, “Delayed Transformational Fatigue in Central and Eastern Europe” and “Populist Rebellion Against Modernity in 21st-century Eastern Europe” (https://populism-europe.com/poprebel/). Kubik served as 2020 President of ASEEES.

Caption for Illustration 1: Photo by Adrian Grycuk - “Gender is death - it kills identity of soul and body”: picketing against gender ideology in Warsaw, November 20, 2014

Caption for Illustration 2: “Fuck off.” A placard from the All-Poland Women’s Strike. https://plakatnastrajk.pl/