Donald J. Raleigh

Education: B.A., Knox College; M.A. Indiana University; Ph.D. Indiana University

Donald J. Raleigh is Jay Richard Judson Distinguished Professor of History at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

When did you first develop an interst in Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies?

I trace my interest in things Russian to my childhood on Chicago’s working-class South Side, whose would-be burghers, many with East European backgrounds, had an active fear of communism. Mark Twain Elementary School deserved top marks for terrorizing its impressionable clientele, including me, with endless “duck-and-cover” drills, owing to the Soviet threat. Then there was Roman Catholicism, and the hundreds of hours I clocked-in on my knees praying for the conversion of the atheist Communists. In short, born in 1949, I grew up in “Dr. Strangelove’s America.” At Chicago’s new John F. Kennedy High School, an in-your-face, enthusiastic teacher, Michael Pagliaro, introduced me to Russian history. I got hooked. I majored in Russian Area Studies at Knox College (after accused FBI spy Robert Hanssen had graduated), where a marvelously idiosyncratic Serb named Momcilo Rosic taught me Russian. During my senior year at Knox, I won a slot on the CIEE’s new semester-long language study program at Leningrad State University, which at the time was the only way for college students to gain in-country experience. Despite the execrable living conditions in Dormitory No. 6 and an awful bout of giardiasis, Russia had become a defining feature of my life. That fall, 1971, I enrolled in the Ph.D. program at Indiana, where I studied with Alexander Rabinowitch. Indiana turned out to be a perfect match for my interests, and Alex the ideal mentor.

How have your interests changed since then?

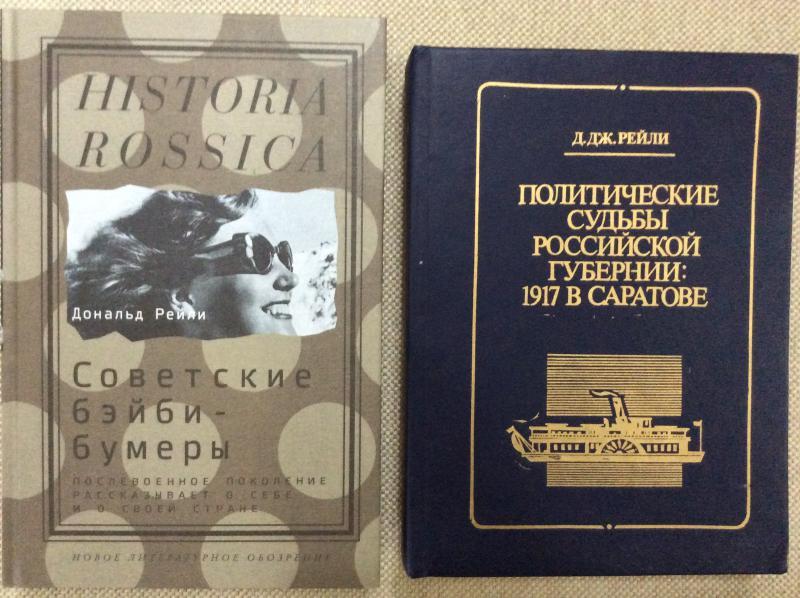

A year-long research seminar that he taught during my second year in the program shaped my research agenda for the next 25 years. When I wrote my dissertation on the Revolution of 1917 in Saratov,  local history remained at a formative stage in the field of Russian studies, because the closed nature of Soviet society had rendered the country’s heartland invisible. But the end of Soviet power now made it possible to carry out research in local archives. In fact, I had begun writing a book on the Russian Civil War based mostly on published sources when, owing to perestroika, I was allowed to travel to Saratov for the first time and to work in its archives. My appetite whetted, I started the project over, resulting in ten more trips to the city. The personal accounts I used in researching the book and grappling with issues of memory and remembering made me receptive to oral history—also, at the time, in its infancy in our field. Since Russian citizens had begun talking publicly about their past, I saw obvious benefits in listening in. I thus added oral history to my methodological toolkit, resulting in a book on Soviet baby boomers, published in 2012.

local history remained at a formative stage in the field of Russian studies, because the closed nature of Soviet society had rendered the country’s heartland invisible. But the end of Soviet power now made it possible to carry out research in local archives. In fact, I had begun writing a book on the Russian Civil War based mostly on published sources when, owing to perestroika, I was allowed to travel to Saratov for the first time and to work in its archives. My appetite whetted, I started the project over, resulting in ten more trips to the city. The personal accounts I used in researching the book and grappling with issues of memory and remembering made me receptive to oral history—also, at the time, in its infancy in our field. Since Russian citizens had begun talking publicly about their past, I saw obvious benefits in listening in. I thus added oral history to my methodological toolkit, resulting in a book on Soviet baby boomers, published in 2012.

What is your current research project?

To date, my current book project—a biography of L. I. Brezhnev—has taken me to archives in Moscow and Chisinau. During the summer of 2016, I’ll carry out research in Almaty.

What do you value about your ASEEES Membership?

It’s been said that, when the student is ready, the teacher will appear. I, for one, am fortunate to have had outstanding mentors and role models throughout my career. I am also grateful for the ASEEES, my “home” professional organization. I’ve missed only three annual meetings since 1975, and look forward to each year’s conference, not only to hear papers and browse the book exhibit, but, as importantly, to see old friends, including former students, whose professional accomplishments bring me great satisfaction.