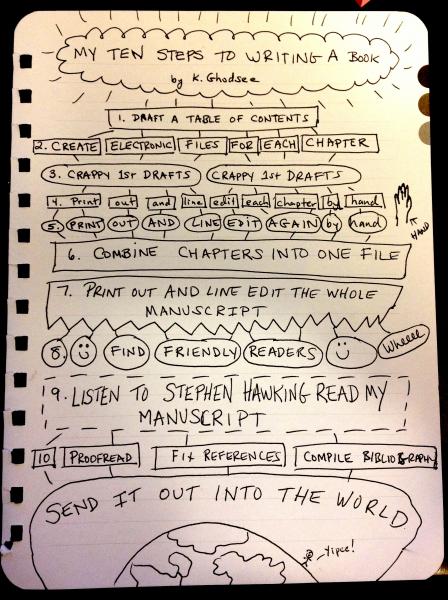

Writing a Book in Ten Steps

by Kristen Ghodsee, John S. Osterweis Associate Professor of Gender and Women's Studies, Bowdoin College

Although I am an academic, I also like to think of myself as a writer since some of my job requires the steady production of the printed word. Over the years, I’ve developed different habits and rituals that help me stay on top of my various writing commitments. In recent months, I completed a fifth book manuscript, and I started thinking a lot about how I write a book from start to finish. It turns out that I have 10 pretty well defined steps, and Lynda Park has asked me to share them on the ASEEES blog. This piece originally appeared on the Savage Minds blog.

1. Produce an imaginary TOC

When I have an idea for a book, I type out an imaginary table of contents (TOC). I think about the overall argument, and how to best organize the material that I will need to substantiate that argument. At this stage I make a preliminary plan about the number and the style of the chapters. For more traditional academic books, I go with fewer, but longer chapters that are organized thematically. For projects aimed at undergraduate students or general readers, I have a greater number of short chapters and prefer a more intuitive chronological organization of the manuscript. Although this outline changes, the intellectual work that goes into its initial production helps me think through the big questions of audience, tone, and length before I start writing.

2. Create electronic files

After I have the TOC, I create a separate document file for each of the chapters, as well as for the front matter, the acknowledgements, and any appendices. Then I cut and paste in any preexisting writing that I’ve done. I call this “found text,” and I include everything that might be relevant to the chapter: journal articles, essays, book reviews, fieldnote excerpts, emails, outtakes from previous books, etc.

3. Write crappy first drafts

Whether I’m building around “found text” or starting from scratch, I write a crappy first draft (CFD) of each chapter. I don’t always do them in order, but I do not edit any individual chapter until I have CFDs of all chapters. These first drafts are appalling, but writing a chapter draft from start to finish without worrying about the grammar or coherence allows me to concentrate on the ideas and emotions that I want to convey. No one ever sees these drafts; I delete them all once I start revising.

4. Print out and line edit each of the chapters

I edit by hand (with a fountain pen) on paper. Editing on screen is more efficient and environmentally friendly, but it makes for lazy writing. Line editing in print forces me to read through the entire chapter before making changes to the electronic file. This allows me to keep the larger structure of the chapter in my head, and to see how the pieces might work better in a different order. This round of line edits is tedious because it is my initial crack at correcting the serious deficiencies of the crappy first draft.

5. Print out and line edit again

I repeat the process above. The chapters are still rough, but after this round of line edits, they start to become readable. At this stage, I focus on grammar, syntax, and narrative flow. I start watching for typos and think about topic sentences and paragraph length. I also consider how my arguments develop over the course of the chapter, and what additional material I might need to substantiate my claims. Only after I have everything down on paper do I input the changes into the computer.

6. Combine the chapters into a manuscript

After the second round of line edits, I go back to my table of contents and think about the overall structure of the book. Some chapters have outgrown themselves, and must be divided in two. Orphaned chapters find new homes or get cut altogether. All of the text that gets slashed is dumped into an electronic “outtakes” file. This serves as a reservoir of “found text” for future projects. All of the chapters are now combined into one electronic file.

7. Print out and line edit

Call me a murderer of trees. I print out the entire manuscript and do a full round of line edits by hand once more. I concentrate on overall coherence and clarity, and look for more material to cut. The manuscript begins to feel like something that I can share with the world without dying of shame.

8. Find friendly readers

My mom, my partner, my friends, and nonjudgmental colleagues are my first line of readers. At this point, I’ve usually been working too intensely and for too long on the project. I need some critical distance. Giving the whole manuscript to a few trusted interlocutors allows me to take a break and get some much-needed external input. Are my arguments clear? Is there still surplus prose? How many typos have I missed?

9. Listen to Stephen Hawking read my words

Once I have incorporated all of the friendly suggestions, I use the “speech” function in Microsoft Word to have my computer read me the entire manuscript. Unwieldy syntax, overused words, and even simple typos are more easily heard than seen.

10. Complete references and send it off

The final task is to organize all of the references and the bibliography. Careful attention to the references allows me to review the overall structure of the book and think about the literature to which I will be contributing. Only once the references are in order will I begin to contact editors. At this point, the manuscript is ready for blind review. I say a little prayer, send it off, and start work on my next project.

Kristen Ghodsee is the author of The Red Riviera: Gender, Tourism and Postsocialism on the Black Sea(Duke University Press, 2005), Muslim Lives in Eastern Europe: Gender, Ethnicity and the Transformation of Islam in Postsocialist Bulgaria (Princeton University Press, 2009), Lost In Transition: Ethnographies of Everyday Life After Socialism (Duke University Press, 2011), Professor Mommy: Finding Work/Family Balance in Academia (Rowman & Littlefield, 2011), and numerous articles on gender, nostalgia, and Eastern Europe. Her new book, The Left Side of History: World War II and the Unfulfilled Promise of Communism in Eastern Europe, is forthcoming with Duke University Press in 2015. She blogs about ethnographic writing at Literary Ethnography.